SARS-CoV-2: Patient surge consideration and control of hospital and healthcare facility airborne infectious disease transmission through HVAC systems

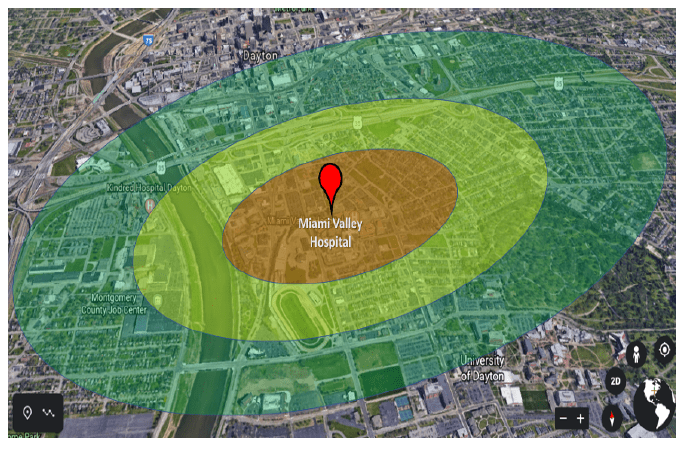

Transitioning hospital HVAC systems to 100% outside air, no recirculation, is limited to only units designed for this accommodation. Increasing the ACH to create additional negative pressure rooms, floors, or facilities is a viable alternative, but only within the performance limits of the existing systems’ design. Note that in both scenarios, the heating and cooling capacities of the units will fall short of temperature and humidity requirements because they are operating outside of their original design parameters. Increased exhaust rates will exceed filtration, ionization, and UVGI design parameters and the ability to scale up these components will most likely be limited by supply chain constraints. Effective mitigation of aerosolized virus spread from these facilities must be determined to ensure that the expelled air is not a hazard to the surrounding community. As referenced from The New England Journal of Medicine (17Mar2020), “results indicate that aerosol and fomite transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is plausible, since the virus can remain viable and infectious in aerosols for hours and on surfaces up to days.”

As the number of COVID-19 patient admissions increases, the need to distance and safeguard uninfected patients from the virus is critical. Alternative facilities will need to be identified and converted for this purpose, i.e. hotels, arenas, assembly-type spaces, etc. The mechanical systems’ capabilities, site location, and facility layout are but a few considerations that are used to determine viability. Developing a standardized strategic plan and decision matrix will help communities expedite the facility downselection process and understand tradeoffs associated with each location. A collaborative effort between the civilian medical community, local government officials, engineers, and facilities groups coupled with Expeditionary Medical Support System (EMEDS) subject matter experts can quickly define this trade-space.

https://fgiguidelines.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/2001guidelines.pdf

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMc2004973

https://www.ashrae.org/file%20library/about/position%20documents/airborne-infectiousdiseases.pdf